Flux coordinates: Difference between revisions

| Line 63: | Line 63: | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

It can be seen that <ref name='Dhaeseleer'></ref> <math>g \equiv \det(g_{ij}) = J^2 \Rightarrow J = \sqrt{g}</math> | It can be seen that <ref name='Dhaeseleer'></ref> <math>g \equiv \det(g_{ij}) = J^2 \Rightarrow J = \sqrt{g}</math> | ||

=== Some surface elements === | |||

Let <math>S_\phi</math> a surface defined by a constant value of <math>\phi</math>. Then, the surface element is | |||

:<math> | |||

d{\mathbf S}_\phi = \mathbf{e}_\psi\times\mathbf{e}_\theta\d\psi d\theta | |||

</math> | |||

=== Gradient, Divergence and Curl in curvilinear coordinates === | === Gradient, Divergence and Curl in curvilinear coordinates === | ||

Revision as of 18:21, 7 September 2010

General curvilinear coordinates

Here we briefly review the basic definitions of a general curvilinear coordinate system for later convenience when discussing toroidal flux coordinates and magnetic coordinates.

Coordinates and basis vectors

Let be a set of euclidean coordinates on and let define a change of coordinates, arbitrary for the time being. We can calculate the contravariant basis vectors as

and the dual covariant basis defined as

where are cyclic permutations of and we have used the notation . The Jacobian is defined below.

Any vector field can be represented as

or

In particular any basis vector . The metric tensor is defined as

The metric tensors can be used to raise or lower indices. Take

so that

Jacobian

The Jacobian of the coordinate transformation is defined as

and that of the inverse transformation

It can be seen that [1]

Some surface elements

Let a surface defined by a constant value of . Then, the surface element is

- Failed to parse (unknown function "\d"): {\displaystyle d{\mathbf S}_\phi = \mathbf{e}_\psi\times\mathbf{e}_\theta\d\psi d\theta }

Gradient, Divergence and Curl in curvilinear coordinates

The gradient of a function f is naturally given in the contravariant base vectors:

The divergence of a vector is best expressed in terms of its contravariant components

while the curl is

given in terms of the covariant base vectors, where is the [[::Wikipedia:Levi-Civita symbol| Levi-Civita]] symbol.

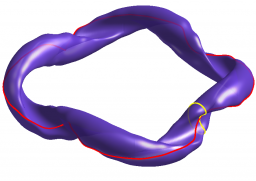

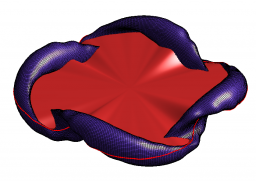

Flux coordinates

A flux coordinate set is one that includes a flux surface label as a coordinate. A flux surface label is a function that is constant and single valued on each flux surface. In our naming of the general curvilinear coordinates we have already adopted the usual flux coordinate convention for toroidal equilibrium with nested flux surfaces, where is the flux surface label and are -periodic poloidal and toroidal-like angles.

Different flux surface labels can be chosen like toroidal or poloidal magnetic fluxes or the volume contained within the flux surface . By single valued we mean to ensure that any flux label is a monotonous function of any other flux label , so that the function is invertible at least in a volume containing the region of interest. We will denote a generic flux surface label by .

To avoid ambiguity in the sign of line and surface integrals we impose , the toroidal angle increases in the clockwise direction when seen from above and the poloidal angle increases such that .

Flux Surface Average

The flux surface average of a function is defined as the limit

where is the volume confined between two flux surfaces. It is therefore a volume average over an infinitesimal spatial region rather than a surface average. To avoid confusion, we denote volume elements or domains with the calligraphic . Capital is reserved for the flux label (coordinate) defined as the volume within a flux surface.

Introducing the differential volume element

or, noting that , we have and we get to a more practical form of the Flux Surface Average

Note that , so the FSA is a surface integral weighted by :

Applying Gauss' theorem to the definition of FSA we get to the identity

Useful properties of FSA

Some useful properties of the FSA are

In the above . Some vector identities are useful to derive the above identities.

Magnetic field representation in flux coordinates

Contravariant Form

Any solenoidal vector field can be written as called its Clebsch representation. For a magnetic field with flux surfaces we can choose, say, to be the flux surface label

Field lines are then given as the intersection of the constant- and constant- surfaces. This form provides a general expression for in terms of the covariant basis vectors of a flux coordinate system

in terms of the function , sometimes referred to as the magnetic field's stream function.

It is worthwhile to note that the Clebsch form of corresponds to a magnetic vector potential (or as they differ only by the Gauge transformation ).

The general form of the stream function is

where is a differentiable function periodic in the two angles. This general form can be derived by using the fact that is a physical function (hence singe-valued). The specific form for the coefficients in front of the secular terms (i.e. the non-periodic terms) can be obtained from the FSA properties .

Covariant Form

If we consider an equilibrium magnetic field such that , where is the current density , then both and and the magnetic field can be written as

where is identified as the magnetic scalar potential. Its general form is

Note that is not the current but times the current. The functional dependence on the angular variables is again motivated by the single-valuedness of the magnetic field. The particular form of the coefficients can be obtained noting that

and choosing an integration circuit contained within a flux surface . Then we get

If we now choose a toroidal circuit we get

here the superscript is meant to indicate the flux is computed through a disc limited by the integration line, as opposed to the ribbon limited by the integration line on one side and the magnetic axis on the other that was used for the definition of poloidal magnetic flux above these lines. Similarly

Contravariant Form of the current density

Taking the curl of the covariant form of the equilibrium current density can be written as

By very similar arguments as those used for (note that both and are solenoidal fields tangent to the flux surfaces) it can be shown that the general expression for is

Note that the poloidal current is now defined through a ribbon and not a disc. The two currents are related as implies

where the integral is performed along the magnetic axis and therefore does not depend on . This can be used to show that a expanded version of is given as

Magnetic coordinates

Magnetic coordinates are a particular type of flux coordinates in which the magnetic field lines are straight lines. In mathematical terms this implies that the periodic part of the magnetic field's stream function is zero in these coordinates so the magnetic field reads

Now a field line is given by and .

Note that, in general, the contravariant components of the magnetic field in a magnetic coordinate system

are not flux functions, but their quotient is

being the rotational transform. In a magnetic coordinate system the poloidal and toroidal components of the magnetic field are individually divergence-less.

Transforming between Magnetic coordinates systems

There are infinitely many systems of magnetic coordinates. Any transformation of the angles of the from

where is periodic in the angles, preserves the straightness of the field lines (as can be easily checked by direct substitution). The spatial function , is called the generating function. It can be obtained from a magnetic differential equation if we know the Jacobians of the two magnetic coordinate systems and . In fact taking on any of the transformation of the angles and using the known expressions for the contravariant components of in magnetic coordinates we get

The LHS of this equation has a particularly simple form when one uses a magnetic coordinate system. For instance, if we write in terms of the original magnetic coordinate system we get

which can be turned into an algebraic equation on the Fourier components of

where

and .

Particular choices of G can be made so as to simplify the description of other fields. The most commonly used magnetic coordinate systems are:

[1]

- Hamada coordinates. [2][3] In these coordinates, both the magnetic field lines and current lines corresponding to the MHD equilibrium are straight. Referring to the definitions above, both and are zero in Hamada coordinates.

- Boozer coordinates. [4][5] In these coordinates, the magnetic field lines corresponding to the MHD equilibrium are straight and so are the diamagnetic lines , i.e. the integral lines of . Referring to the definitions above, both and are zero in Boozer coordinates.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 W.D. D'haeseleer, Flux coordinates and magnetic field structure: a guide to a fundamental tool of plasma theory, Springer series in computational physics, Springer-Verlag (1991) ISBN 3540524193

- ↑ S. Hamada, Nucl. Fusion 2 (1962) 23

- ↑ J.M. Greene and J.L Johnson, Stability Criterion for Arbitrary Hydromagnetic Equilibria, Phys. Fluids 5 (1962) 510

- ↑ A.H. Boozer, Plasma equilibrium with rational magnetic surfaces, Phys. Fluids 24 (1981) 1999

- ↑ A.H. Boozer, Establishment of magnetic coordinates for a given magnetic field, Phys. Fluids 25 (1982) 520